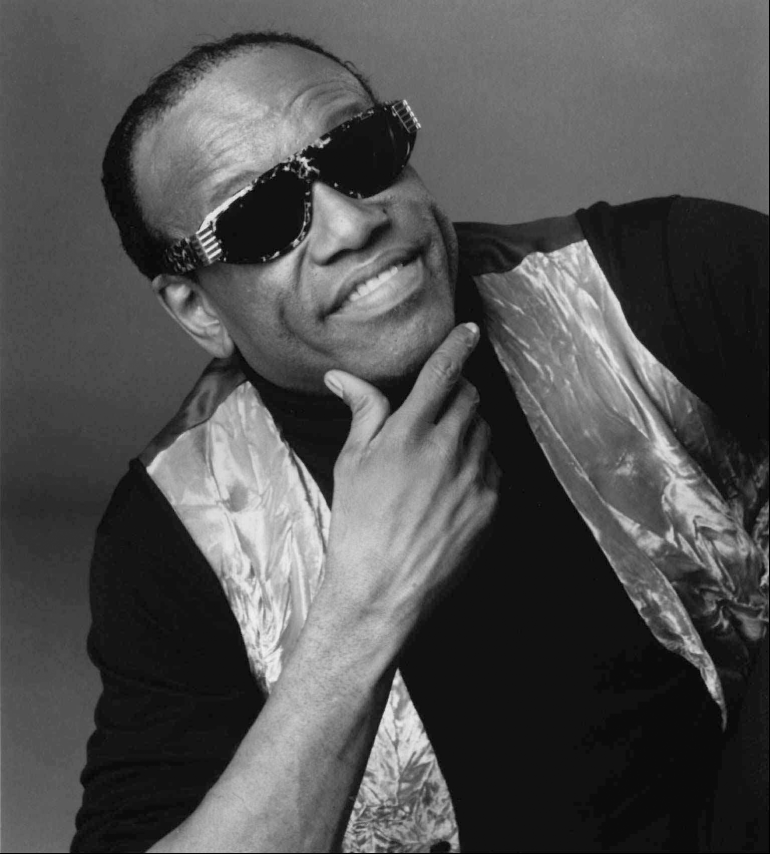

In August 1994, Echoes Editor Chris Wells flew to Los Angeles to record some interviews. Whilst there he looked up Bobby Womack, whom he’d heard had been working on a new album for Rolling Stone Ronnie Wood’s Slide Music label. The resulting encounter – including a wild car chase through the Hollywood Hills – became one of our most widely read features. Here it is in full, for the first time on our website.

I’d been tracking Womack for two-and-a-half days. His number had changed. I’d been up to his house in the Hollywood Hills only to be greeted by a locked door, a decidedly nervous female voice, a growling Alsation and the information that, ‘He moved out a year ago’.

Finally, around six hours before I’m due to depart for San Francisco, Bobby’s friend and writing/production partner Patrick Moten – himself just back from a weekend’s live work in Cleveland, Ohio with Gerald Albright – updates my address book. Minutes later Bobby’s familiar growl is on the line, issuing an invitation to his new office/apartment in Sherman Oaks.

He’s specified 4pm. Ever the enthusiast, I arrive early to find Womack on the street about to step into his white Pontiac Grand-Am. It’s a sleek, little, low-slung affair that once belonged to his father and which he’s recently had rebuilt. As I’m later to discover, it flies. It turns out that Womack has a sudden need to wire some money to his wife, Regina, and must visit his bank right away.

Bearing in mind the tight schedule, the only sensible option is to conduct the interview as he drives. We accelerate – rapidly – to the traffic lights. We accelerate to the next set too. On a whim, Womack cuts a fast U-turn to a shop he wants to visit. Then he cuts another and we turn south off Ventura Boulevard, heading back over the Hollywood Hills along Laurel Canyon. It’s a impressively scenic route, although its somewhat switchback nature prompts me to remember that its history also includes a fatal crash involving Luther Vandross.

Better get on with it, then: Why had he moved house?

“I went through a divorce. My old lady left and took the kids, took my wallet and the pants it was in. Really, it was the worst thing I have ever experienced… and that’s something, ‘cause I’ve lost a brother, two sons…

“I’d been seeking a woman who could give me that homebase. I thought Regina would give me that. But I forced her into the situation. She was a waitress, not doing a whole lot. I told her I could help her live better – I could give her all the things she wanted, if she lived with me. I wanted her to make a family, so’s when I got off the stage I could go home to them. But you can’t make it happen.

“She said she loved me… then one day, after 18 years, she says she wants to know who she is, if she can go on without me. I told her she could do anything she wanted but leave.”

It’s an opening salvo of honesty and genuine regret, and it takes me by surprise. Anyone following Womack’s many and varied adventures over the years expects something dramatic to have happened to this most colourful of soulmen, but this latest episode has clearly knocked out some stuffing. It hasn’t caused him to roll over and die, though. He has too much fight for that.

“I went to Japan,” continues Bobby, “to get over what happened and to work. I got to thinking that if maybe I’d left with some of the other guys of my era – guys like Sam Cooke, David Ruffin, Eddie Kendricks – then I wouldn’t have to keep coming back all the time. But I refuse to leave! There’s nothing else in this world for me to do.

“Listen, I feel like I got mud in my eye now. All you Michael Boltons, get your bags packed and head for the hills. Take as much as you can carry and get the fuck out, ‘cause I’m gonna show you the real deal. This new album is called Resurrection, and if I’m gonna call it that then I’m gonna have to live it. I had to wipe out all of the drugs, the alcohol, the cigarettes… anyway, doctor says I’ll die if I don’t.”

At 50, Womack’s preoccupation with death occasionally competes with his desire to gain the respect of a music industry that all too readily turns its back on a maverick talent such as his. And he’s come back before: The Poet and Poet 2 albums resuscitated his dormant career at the beginning of the eighties, a time when all but his legion of loyalists had given up on him. Instead he spent the latter part of the decade signed to MCA, releasing a trio of albums – So Many Rivers, Womagic and The Last Soulman – each less successful than its predecessor. His most recent album, at the decade’s turn, was for Epic, the largely overlooked Save The Children. Perhaps the last recorded moment we all approved of was his new version of I Was Checkin’ Out, She Was Checkin’ In, cut for a Don Covay tribute album last year.

We’re heading downhill towards Sunset and Womack picks up the theme.

“I went to see Don Covay. We’d always get together and talk about who died: ‘Man, they found him like this… ’

“I couldn’t talk to Pickett, ‘cause he’d been in jail. Anyways, you never know which Pickett you’re gonna get these days. One time I called him and he says, ‘Bobby, you know I love ya, but don’t call me no mo’.’ Weird shit.

“Anyhow, I couldn’t talk to Don for a while ‘cause he’d had this stroke and he was in a coma. I’d sit next to his bed and beg him, ‘You big mouthed motherfucker, why don’t you say something?!’ Then one day the phone rings and this voice says, ‘Hey, it’s Don. How you doin’?’ He’s asking how long he’s been out and who died! Well, he’d been out of it two years, so there had been a few.”

Amongst the latest was Bobby’s favourite studio engineer, Barney Perkins, a guy whose bear-sized body finally put too much strain on his heart during last winter. He’d been working on Resurrection at the time.

At last we pull up outside a branch of Wells Fargo just south of Sunset, opposite the CBS TV studios. Bobby greets its manageress with all the bonhomie you’d normally reserve for a long lost sister. She turns out to be Irene Gay, wife of Frankie and so sister-in-law to Marvin. As we’re waiting for the transactions to go through, Womack tells me the truth behind recent reports of his severe throat problems.

“For the first time in my career my voice gave out on tour,” he says. “I’ve had nodes and other stuff, but never once did my voice just refuse to come out. I had to cancel some sold-out shows at the Beacon Theatre [in New York] because of it – lost thousands.

“I went to the doctor and he told me it was my lifestyle. He knew I hadn’t been following his orders. He’d told me to cut out the alcohol before and I’d just been sweatin’ it out in the sauna before I went to see him. But he was smarter than that: he told me I wasn’t foolin’ nobody but myself. He said he could give me a cortisone injection if I wanted and that it would deaden the pain, but if I went on putting this kinda strain on my voice it could cut out for good. That scared me, man.

“But we finished up the tour. Some nights I couldn’t sing my whole programme, so I did whatever I could. One night, out in Oklahoma City, I had to get off stage after six songs ‘cause I couldn’t make a single sound. Some guy, a big mutha about seven feet tall, burst into my dressing room with three of his buddies. ‘Hey nigga’, he says, ‘get your yo’ ass back out there now!’ I pulled my gun out from under my coat and stuck it on the guy’s forehead – backed ‘em out like Gladys Knight and The Pips doing a routine! Later, the manager comes in to see what’s been going down. When I take him by the hand I give him the special handshake and suddenly it’s, ‘OK, Mr Womack, you’ll have no more problems’.”

Special handshake? Believe it: Bobby Womack is a freemason. No joke. So is Patrick Moten. So was Bobby’s father. Womack Jr decided to join the brotherhood after a childhood incident in which the family car broke down in rural Georgia and a bunch of rednecks responded to his father’s mason-style hand signals at the roadside. Recalls Bobby:

“My daddy said, ‘Son, these guys might think we’re the worst bunch of niggers on the planet, but they gotta help us because they swore an oath to help a fellow mason in trouble’. And we had our wheels fixed and were given something to eat while we were waiting. That was unheard of down south back in the fifties.”

Now we’re back in the car, heading north towards Sherman Oaks and my own vehicle. If we step on it I’ll still make the flight. But it’s now well into commuter drive-time and the freeways will be jammed. The only unblocked route will be back through the Hollywood Hills, forsaking the major thoroughfares for the winding back roads. It sounds like a great idea – until this guy in a pick-up truck on Outpost Drive deliberately baulks us, driving at about 5mph in the middle of the road. We can’t get past.

Womack sounds the horn as politely as he knows how and makes to overtake. Suddenly Mr. Pick-Up is all hand gestures and racial abuse. A volley of ‘Fuck you’s is exchanged. He then hurls something that looks like a bottle at us – it misses – calls the flash mutha in the white sports car a ‘nigger’ one more time and guns it for the high ground. An instant later Womack hits the pedal too, causing me to lurch into the back seat. We’re off!

I can see Pick-Up laughing and taunting us as he hangs out of his open driver’s side window. Remembering what happened to Ayrton Senna, I plead with Womack to turn the other cheek. But he’s not listening: he’s lost inside a red mist and bent on retribution.

Screeching around the bends, we soon descend on our prey. [Well, we do have a sports car.] Womack retrieves a soda bottle from between his thighs and aims it at our adversary. It bounces off the guy’s roof. Momentarily distracted, Pick-Up swings wide on a hairpin and in a flash Womack is through on the inside. We speed off. I think it’s over. But it’s not.

We turn right onto an even narrower strip of tarmac known as Firenze Avenue. This is where Womack used to live, so he knows exactly where to pull over and collect a house brick, until then doubling as a garage doorstop. “Let’s settle this now,” he growls. It’s the only thing he’s said in the last 10 minutes.

Just like in the movies, we rejoin Woodrow Wilson Drive right behind Pick-Up, who almost falls out of his vehicle in surprise when he glimpses us in the mirror. We pull alongside, Womack brandishing the brick with clear intent. It’s too much for Pick-Up, whose bravado finally cracks. “Look what you did to my car, man!” he wails, pointing to a stove-in nearside front wing, presumably the result of trying to catch us. Womack laughs contemptuously and turns off left, closing a terrifying little chapter with: “Man, if I’d had my piece, I’d have blown the motherfucker away.”

OK then. I attempt to cool things down by talking about his plans for the new album. Much to my surprise, it works.

So far, guests on Resurrection include all of the Rolling Stones apart from Mick Jagger, Muhammad Ali’s rapping daughter Mae Mae, Slash from Guns ‘n’ Roses, Stevie Wonder and Rod Stewart. There’s a song on there written by the guys from Toto and a country-soul tune called Cousin Henry, based on his uncle’s experiences in Vietnam. There’s a version of the old Winstons hit, Colour Him Father and there are some tributes to Sam Cooke, David Ruffin and Eddie Kendricks. It is, to say the least, a varied work.

Its success is vital to Womack’s future plans. He’s already bought a house out in Blueville, West Virginia. He hadn’t intended to, but on discovering that a dwelling purchased for his mother by brother/sister-in-law singing duo Womack & Womack was about to be foreclosed on for non-payment of mortgage, he found that he had little option. So far Mrs Womack has been the delighted recipient of a new dishwasher, washing machine and stove. Soon she’ll be signing for a swimming pool and jacuzzi, and next year [all being well] for a complete home studio. Bobby’s also invested some money in Martoni’s, an Italian restaurant in LA, not coincidentally the last eaterie visited by Sam Cooke on the night he died.

Signed to Ronnie Wood’s Slide Music label, Womack now pins his hopes on an old friend’s respect for his work. It’s been a bit of a love/hate relationship with The Stones since they recorded It’s All Over Now and hitched themselves a ride on the back of Bobby’s writing talent, so my interviewee’s closing comment feels only just like a joke:

“I told Ronnie that if these songs don’t get heard he could cancel Christmas! I always wanted to kill me a Rolling Stone. Maybe now’s my chance.”